More to come…

More to come…

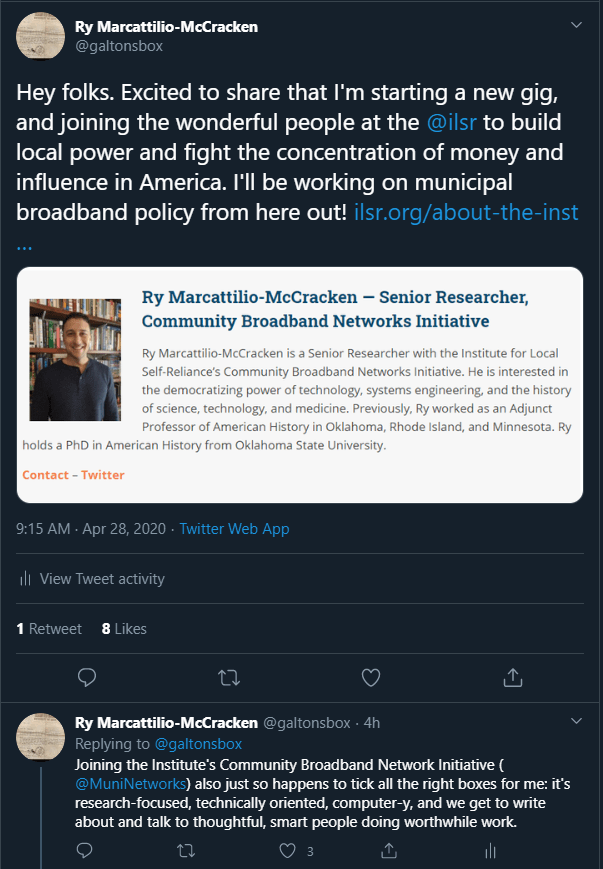

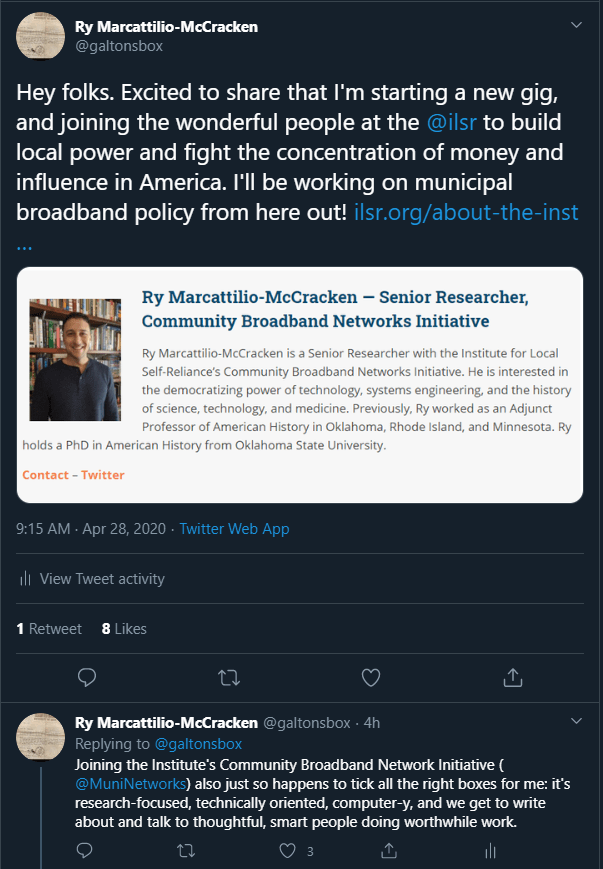

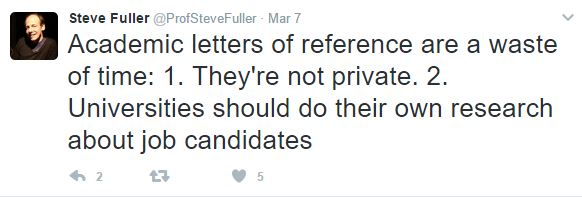

Steve Fuller posted the below the other day, and it put to words a problem I’ve been thinking about for quite some time (being on the job market myself the last two years).

For the record, I agree with Steve (as I do in most instances) a hundred percent about recommendation letters being a waste of time and energy. I can’t believe they’re still used. Thankfully, I’m seeing a dip over the last two years from position searches requiring them on the front end. Hallelujah.

But the search process (at the university level) itself is a unique animal. Let’s recap quickly. The landscape of the job market is a tangled mess: it’s a draining, Sisyphean task to comb through one or two or three hundred applications and pick ten to interview on the phone, and I don’t think it’s a controversial position to say that many, many qualified, good-fit candidates get lost in the shuffle. And it’s a problem compounded by two pretty obvious realities–the aforementioned volume of applicants, and, equally important, the fact that different types of institutions (both structurally and culturally) are looking for different types of candidates. Ivy-league schools want hyper-productive researchers who can also teach and bring in grant money. SLACs want regionally-aware faculty with strong teaching records who understand that sixty percent of their student body are first-generation students, or ethnic minorities, or come from within (and stay within after) a hundred miles of the campus. Community Colleges want candidates who have experience managing sixty-student sections and online surveys and can engage them in meaningful ways, twice each fall, spring, and summer. These needs obviously overlap in many instances.

Yet without a doubt each of the institutions above has some significantly different items on the checklist. The problem is that grad students never get to take a class called HIST 565: What Different Types of Schools Want From You As A Faculty Member. This is, of course, further complicated by the fact that schools themselves sometimes (often?) don’t know or are unwilling to admit that what makes a successful, collegial hire for them as a STEM-focused campus of twenty-seven hundred in a town of ten thousand in rural Georgia doesn’t look the same as a successful hire as UC-Santa Barbara or Valencia Community College. This is bad for both new hires and schools, evidenced (in part) by the fact that so many of the former move on to another school after two or three or four years, forcing another exhausting search.

But I’m not convinced departmental hiring committees can fix this problem without both big money investments from administration and attitudinal changes at the department level, neither of which are likely. Maybe the real question we should be asking is: should they?

There’s a case to be made, I think, that such entities are not, in fact, what we need to find the best candidate to fit for the job–if that is our collective goal. After all, most only do it once every five or ten years. And academics are notoriously terrible at honest self-evaluation–a fact that is, again, not entirely their fault–which means undertaking a search requires identifying, ranking, and assessing skills in a potential colleague is not something they are really built to do.

So, to the point of this post: What about hiring a consulting firm to do the job? As far as I know, job placement works well for other teachers. Why doesn’t it exist for post-secondary institutions? Feel free to correct me here, but I certainly don’t know of any that exist. Seems like a win-win-win. Hypothetical Placement Firm is staffed by individuals with an intimate understanding of what academic disciplines look like from the inside; there is certainly no shortage of them running around. It establishes a network of contacts at the departmental level, so it can have short (and ongoing) conversations about needs, past experience, and successes and failures. It sends someone to major conferences who meets with ABDs and recent grads for thirty minutes to talk CVs, research, teaching experience, and get a sense of interpersonal skills. It builds and retains a portfolio of applications. University of X, Department of Y pays a small yearly fee to Hypothetical Placement Firm and then, when it wants to run a search, it pays a lump sum to get a group of candidates from the firm which spends literally all of its time gauging not only what departments like them needs, but what the market looks like in a given year. The service is free to prospective hires, as is (almost astonishingly) both equitable and economical.

This headhunter model seems like it would work infinitely better to me. Departments spend a little money and save a bunch of humanpower. Faculty don’t have to waste dozens or hundreds of hours–collectively tens of thousands of dollars–that they could put towards, you know, research, curriculum development, fighting the reactionary agendas of legislators and judges, etc. Candidates get more detailed examination of their application portfolios–more than a hundred and twenty seconds in any case. And the most toxic, terrible part of becoming an academic–the job market–gets a little better.

Because here’s the thing that you learn very quickly serving on a search committee–though many candidates look the same on paper, in person they quickly distinguish themselves from one another. This is why job candidates spend roughly four hundred hours being evaluated at a campus visit. Small-group conversation, research presentation, teaching presentation, one-on-one interviews; grad student meetings, faculty meetings, administration meetings. Because when you get right down to it, selecting for the strength of a CV (mostly) and then a cover letter (some smaller remainder) nets you a group that might be academically accomplished but is mostly comprised of inarticulate weirdos, arrogant pricks, misogynists, or slabs of wet cardboard. This is why so many times the person who gets selected as the department’s top choice has so much bargaining power–because the committee has no acceptable backup, as members have vetoed for one reason or another everyone else’s candidacy. The kicker is that the vast majority of the time you can weed out the chaff with a fifteen minute conversation, so long as the interviewer has a plan. Tell me I’m wrong.

In a perfect world Steve is right. But (being familiar with his writing on topics like this) I think he’s being disingenuous about the larger picture in service to his position on university governance and Humboldtian reform. The reality is that the hiring process is mess and the third-party solution offers a viable, and most importantly better, alternative. Persuading faculty of this, however, is different task.

I’ve got a new article out in the Journal of the History of Biology. It’s an historiographical re-examination of the eugenic family studies which were so critical to moving eugenics into mainstream cultural and thinking, with a specific focus on space and place as analytical frameworks.

Abstract:

Though only one component product of the larger eugenics movement, the eugenic family study proved to be, by far, its most potent ideological tool. The Kallikak Family, for instance, went through eight editions between 1913 and 1931. This essay argues that the current scholarship has missed important ways that the architects of the eugenic family studies theorized and described the subjects of their investigation. Using one sparsely interrogated work (sociologist Frank Wilson Blackmar’s “The Smoky Pilgrims”) and one previously unknown eugenic family study (biologist Frank Gary Brooks’ untitled analysis of the flood-zone Oklahomans) from the Southern Plains, this essay aims to introduce “environment” as a schema that allows for how the subjects of the eugenic family study were conceptualized with respect to their surroundings. Geospatially and environmentally relevant constructions of scientific knowledge were central to the project of eugenics during its formative years, but remain largely and conspicuously absent from the critical literature which engages this project to separate the fit from the unfit in American society. The dysgenic constituted a unique human geography, giving us significant insight into how concatenations of jurisprudence as well as cultural and social worth were tied to the land.

Eugenics; Family studies; Environment; Heredity; Human geography

I’ve fully embraced the benefits and strictures of being a professor in the digital age. In both my online courses and live ones, I have come to rely upon our online classroom portal to disseminate course information, post reminders, log grades, and to serve as the primary method by which students turn in their papers. It lets me engage in a variation of the minimal marking I find pedagogically useful, and at the same time avoid the detrimental effects of showering student papers in red. I don’t know if it is necessarily sounder on the balance to do it this way, but it’s a system that’s been honed course after course and seems to work well for both sides of the lectern. No doubt everyone has her/his own preferences and experiences, and certainly the online classroom has fueled plenty of conferences on teaching method since its inception some fifteen years ago. For better or worse, it’s here to stay. For me, at least, and for now.

It’s the last item on the list above that serves as occasion for this piece, for every paper turned into my class dropbox gets automatically run against TurnItIn.com’s plagiarism detection tool. No doubt many of you use TurnItIn, and have for years. I detest purposive plagiarists. They are, for me and no doubt for many of you, the bane of my professional existence. Like so many others, I’ve done my best to stamp it out with anti-formulaic assignment prompts, rotating exams, and gentle reminders through the semester that committing plagiarism invites the devil into your soul. I still get students who, with Machiavellian overconfidence and through abject laziness, plagiarize.

And so if asked, I’ll not pretend otherwise—I love TurnItIn. It’s painless, in my experience effective, and just as importantly, already there for me to use. It saves me some relatively significant number of hours each term, agonizingly Google-searching the paper of a student who has suddenly turned into David Foster Wallace on the final exam. And when I am forced to pursue an instance of academic dishonesty, it provides a nice, tidy, official-looking report that tends to convince students of the authority and weight behind the meeting we are currently having. So I use it, happily.

But recently I got an email from a student concerned about TurnItIn on dual grounds that I’ve assumed would surface at some point. The student was nontraditional, and this was her/his first college course in some years. Having read the paragraph above, s/he was concerned first about accidentally plagiarizing, and wondered (naively, but completely understandably) if TurnItIn let students run their work through for free to make sure this didn’t happen. Secondly, the student (in so many words) didn’t like the idea of being forced to surrender her/his work to a company that would make money off of it. S/he was articulate, respectful, and tentative.

My knee-jerk reaction, which thankfully lasted only a minute or so, was to throw up shields. Tell the student such anti-plagiarism tools were clearly spelled out on our syllabus, and that by staying in the course each student was assenting to such measure in the name of academic integrity. But in typing this into Outlook I decided I should probably be sure this was actually the case, and so I called up our university’s Academic Integrity Coordinator. Funnily (or sadly?) enough, the first thing our coordinator said was she’d been expecting a question like this for some time, but hadn’t gotten it yet (TurnItIn, by the way, has been around since 1997). In the end, the above position was confirmed: so long as it was in my syllabus, I could do what I wanted. I went back to click “send,” and discovered I was ambivalent about it. It must have taken some guts to send that email to one’s professor, and at the very beginning of the semester no less. Plus, the fact that there was no standing university policy pertaining to what was a potentially explosive issue—the “it’s in the syllabus argument” seemed astoundingly soft, in that it relies on student ignorance rather than legal standing—made me curious if anyone had challenged it.

A little searching turned up surprisingly few lawsuits brought against iParadigms, the parent company of TurnItIn. As it turned out, someone had issued a challenge. Six years ago a court weighed in, and the judge ruled in the favor of iParadigms on four grounds:

“1) Commercial use can be fair use, and, citing Perfect 10 Inc. v. Amazon.com Inc., use can be transformative ‘in function or purpose without altering or actually adding to the original work.’ TurnItIn transformed the work by using the papers to prevent plagiarism and not for factual knowledge; 2) The website’s use does not diminish or discourage the author’s creativity or supplant the students’ rights to first publication; 3) Using the entirety of the papers did not preclude fair use; and 4) TurnItIn’s use does not affect marketability.”[1]

I’m not a lawyer. I’m a history professor. But I don’t really buy the “highly transformative” argument (the ruling itself admits they don’t actually change the documents at all but merely “use” the papers in a different way. Probably Derrida would award me a demerit for saying this); nor do I really accept uncritically the “does not diminish or discourage creativity” one. Point four I’ll also take issue with. It completely misses the premise that one doesn’t have to be motivated by market value to produce an original written work (and so that shouldn’t be the standard to retaining full and exclusive copyright). But even acceding to the premise, on TurnItIn’s own terms, should a student want to start up her or his own plagiarism-detection company and use the corpus of her or his own work as a starting point, s/he’d immediately run into the fact that TurnItIn can claim (rightfully) that they already have not only this student’s body of papers but 336 million and change of other student papers. Talk about David vs. Goliath.

No doubt someone will come along and tell me this is a settled issue, legally speaking, which is fine but also not really the larger point of this essay. At this stage, all I’m left with significant questions. Do I keep feeding the beast, or try some alternative? To what extent, if at all, have we as professors crossed an ethical line by blithely becoming complicit in this model over the last decade—such that TurnItIn is the only name in the game—and we’re now beholden to them in every practical way? It’s the flagship service of what is almost a billion-dollar company, after all, with annual earnings of fifty million a year. Do plagiarism detection services in and of themselves contribute to a fallacious notion of original authorship when in fact the whole endeavor is much more complicated than we’d like to admit when marking first-year student papers?

It also made me wonder how many other concerned students there were peppered among the undergraduate body, and how professors engaged them. Why hadn’t the university’s academic integrity coordinator ever run into this issue before? If we’re supposed to be fostering the next generation of critical, engaged citizenry not only able but willing to step up to bat for themselves on issues such as these, we must be failing in some sense or another.

These are all questions everyone who has either taken or taught a class which used TurnItIn has no doubt wrestled with at some point. In the end, I told the student I was sympathetic to the argument, and if s/he wanted to send me her/his papers instead of uploading them (since I can’t individually turn the detection function off) I’d take them that way. I’d have to check them manually still, I wrote, but it was a time investment I was willing to make given when I now knew. But this avenue won’t work as soon as two or five or ten more students email me with the same concerns, and so it’s not a long-term solution. It’s Band-Aid, and a relatively weak one. It won’t stick for very long. Eventually, I’ll have to decide which is more important: my time, or any overriding philosophical concerns. And I know which one gets rewarded on a daily basis, and that leaves me uneasy, to say the least.

This essay originally published at the Chronicle of Higher Education, September 8, 2015.

[1] Hakimi, Sharona. “To Students’ Dismay, Plagiarism Detection Website Protected by ‘Fair Use,’” Harvard Journal of Technology and Law, April 25, 2009. http://jolt.law.harvard.edu/digest/copyright/av-v-iparadigms-llc

One of the fallacies perpetrated by the age of digitization is that anything worth scanning into an online database already has been. This is, of course, laughable. Even the most well-funded research libraries (or should I say, particularly the most well-funded research libraries) have cubic fathoms of storage space taken up by the superfluous, the redundant, the extant, and the strange. Ask any historian who’s done sustained archival research about the weirdest thing s/he has seen and you’ll get a good story. Probably it won’t even be related to the kind of work s/he does, but something stumbled upon by accident. Archival research is in many ways a weird endeavor–its feels like going through somebody’s mail in a way, even though you know the box in front of you was donated expressly for those who come after to try and make some sense of that which came before. We are so often the poorest judges of the lives we lead.

I’ve come across plenty of strange stuff, both of the why-the-hell-would-someone-keep-this and the what-in-the-name-of-Zeus-is-this variety. Electrician repair bills from the late 1920s with line items that compel me to believe said house burned down shortly thereafter, strange pictures of animals or vistas with no accompanying context or explanation, written ephemera that is both bizarre and disturbing. That kind of thing. Inevitably it makes me wonder what kind of picture would emerge of my life if all someone had was a dozen boxes of the stuff that defined my life in all its intention, abstraction, and banality.

The pamphlet pictured above is neither of the former, but of a different class of material culture history. Despite little evidence of a measurable market–academic or otherwise– and the de-legitimization of its premises by both genetics and changing cultural norms, it simply refused to go away. A testament to that fact is that its author, Kansas-born artist Corydon Granger Snyder, self-published 8 editions between 1928 and 1952.

Most of the time, anthropometry is discussed as a late-nineteenth or early twentieth-century phenomenon with perhaps its best-known footprints laid in craniometry, phrenology, and criminology, though it remained a practice with a far longer arm across the world than is commonly acknowledged even by historians of science and medicine (chronologically, intellectually, and institutionally). Snyder’s little text is proof of an incarnation which remained intimately bound with another scientific bogeyman of the first half of the twentieth century: eugenics.

Split into roughly halves, the first section of the text above sets the foundation for the second and proposes three roughly discrete but interlocking projects to be undertaken: first, that there exists an objective, quantifiable, and universally valid notion of beauty; second, that society can, and should, strive to increase its number of beautiful people and (its inevitable corollary) decrease the number of “homely” people; and third and finally, that the mechanism by which to achieve this project exists if we combine the aesthetic and tools of classical art and those of the science of genetics.

To effect greater numbers of the beautiful, regular, and proportional continues in the 1952 edition the motivation behind the first edition of the text, and is expressed in its original 1928 title: Beautiful Children from Homely Parents: If They Are Opposites (1928). It also serves as a bridge to the dual problems, in Snyder’s estimation, that his project solves: first, one which provides a systematic and authoritative exploration of beauty as it relates to type, and both as they impact reproduction. Throughout the course of the pamphlet is becomes abundantly clear that his underlying concern also engages the eugenic impulse and thus places Art and Human Genetics next to other neo-eugenic Malthusian treatises of the postwar era (like Fairfield Osborn’s Our Plundered Planet and William Vogt’s Road to Survival, both published in 1948). Just one excerpt that demonstrates this comes midway through:

It is hardly desirable in this day and age to breed a race of giants. In fact it has been stated by scientists that in the not far distant future it may be necessary to breed a smaller race in order to offset the fast diminishing food supply. It is to be hoped, however, that before that time we have a rational birth control.

Eugenics–even more than most intellectual movements–was polysemic its heyday; following it into the postwar world demonstrates how adaptable ontologies of hereditary worth which confound simple chronological, disciplinary, and rhetorical categorization really were.

The casual reading might erroneously suggest that, despite half its title, in fact there is little genetics contained within. There is no discussion of genetic mutation, alleles, or population statistics. But a closer look reveals that Snyder in fact remains very much concerned with the particulars of how genetics might be marshalled to improve the human race. Four short quotations illustrate this. On regression towards a mean, he writes:

In writings on eugenics a great deal has been said regarding height, color of hair and eyes, but little on the feature and nothing on the possibility of opposite extremes equalizing the features and creating a normal type in their offspring.

Again on regression, as a caption to profile sketches of a nuclear family with three children, he asserts (capitalization in original):

When EACH of the parents has one or more IRREGULAR features, but which are OPPOSITE to each other’s, the children will have features that are more nearly REGULAR than either of the parents.

One more time on regression, but with some injection of Mendelian inheritance:

Coming back again to the matter of facial proportions, let us first consider the fact that the children of parents having opposite extremes in features may quite closely resemble one of the parents. The chances are that at least one in three will. Nevertheless, there will be some correction towards the regular type of features. And in another generation, care in respect to any objectionable feature will remove it entirely as a family tendency.

Lastly, a clearer formulation of Mendelian inheritance, from the standpoint of art:

When one parent has REGULAR features, and the other parent has ONE or more IRREGULAR features, the children will all resemble the IRREGULAR FEATURED parent. This is because the REGULAR FEATURED parent is really a NEUTRAL, and has little or no effect in modifying the IRREGULAR features of the other parent.

Snyder’s terminology here is easily translatable to the realm of genetics, with “neutral” indicating a heterozygous parent (with one dominant and one recessive gene), and “regular” and “irregular” indicating pure recessive and dominant homozygosity, respectively. It appears that “irregularity” is the dominant trait for Snyder, for even one irregular feature dooms the next generation to the same irregularity of features. The text itself is bracketed by diagrams showing the measuring of heads, and the second half of Art

It might seem to some that Art and Human Genetics is nothing more than a peculiarly archaic but ultimately harmless pamphlet, the work of a self-employed artist at the twilight of his career feeling left behind in the modern world. But what lies behind this seemingly nostalgic but facile treatment of opposite types and marital compatibility is in actuality nothing less than an attempt to unearth the racial typology of physical anthropology, phrenology, and their far more insidious progeny: eugenics.

And so tracing individuals like Snyder after World War Two allows us to follow eugenic notions and arguments with a flashlight as they scurried to inhabit new disciplinary frameworks and discourses in the post-WWI world. To say eugenics in America after 1945 existed as a shadow of its former self is both far from and tantalizingly close to the truth; it would be far more accurate to say postwar eugenics existed as shadows of its former self, conspecific incarnations which broke off to occupy new intellectual and cultural spaces. The move was painful, cladogenetic, and rife with the ghosts (both literally and figuratively) of the past. But eugenics was a powerful idea. And ideas, unlike life, are not so easily destroyed.

Audrey Truschke over at Dissertation Reviews recently posted up a lengthy essay to junior scholars worried about the impact of letting their dissertations roam about, unfettered, in the wild. And various people seem to think it’s something we should all pay attention to. Well-written it is, and chock-full of data as well. The crux of Truscke’s argument (though you should go read it yourself): newly minted PhDs who worry about letting their research live in open-access land while they furiously try to turn their dissertation into a first book are wasting their mental time and energy. There’s no reason to worry. Unfortunately, little persuasive proof is marshaled in defense of this position, while simultaneously–and here’s the kicker–nothing is done whatsoever to show that embargoing one’s dissertation is detrimental to one’s status as a junior scholar.

Much of her discussion will be familiar to those of us who follow this topic with some measure of regularity. Truschke’s ace-in-the-hole here is that she spoke to “university press editors” themselves to ascertain how they operate–both in theory and praxis–from first books. To be fair she manages to glean some useful information from pressing her interviewees. We discover, for instance, that this lingering sense of “it’s already out there so folks won’t buy it” plagues university press editors just like the rest of us dialed into this conversation. This itself remains a potent data point. We learn some specific bits about how the dissertation and first book are very different animals (“cut the literature review, reduce the notes by one-third, spend less time directly quoting other scholars, write better, have a punchier and broader argument, and make the introduction and conclusion more dynamic”). We learn also a little about the behind-the-scenes operations of the book contract itself, which is interesting but really not all that relevant.

The problem with Truschke’s piece is that she manages to minimize those data that are cause for concern, ignore any kind of cost-benefit analysis, fails to critically analyze the other side of the equation, and in general mucks up this conversation further with a bunch of white noise.

For instance, she cites a 2011 study:

“a mere seven percent of university press editors said they would refuse to consider a book based on a thesis that had been made previously available in an electronic repository . . . [though] there is good reason to question whether even that seven percent actually act as they claim.”

I disagree vehemently with the word “mere” in there. 7% is plenty high enough in this current academic climate (just as it was when I first read this study three years ago) to be worried about, acted upon or not. If I can do something as little as click a button and dramatically increase my chances at a book contract with 7% of editors with nothing on the debit side of that balance sheet, and you think I won’t do it, you have an ill-informed sense of the pressures I currently face in the academic job market. But let’s go along with Truschke for a moment, and entertain her larger point: that even if these editors say they don’t consider open-access dissertations for first books, in practice they often won’t look for it/compare them. At this moment, even if I concede she’s right in ninety percent of cases, that still means I can increase my chances with .7% very easily. I’ve done a lot more for a lot less.

Secondly, her evidence to the contrary ends up boiling down to: these editors told me they don’t bother looking at the online version of a then-dissertation and now-manuscript, because it would be a waste of time. They’d rather trust their own judgment that what sits in front of them remains substantially changed from its original form. Something about years of experience that the revision process from both ends will substantially change any work (certainly true to an extent, I’m sure). But that’s where Truschke stops, and ultimately its what’s left unsaid that jumps off the page. There’s a prominent negative space which puts the reader in the difficult position of concluding either dissertations and first books actually are so dissimilar that it really would be a waste of time (something in History, especially, we pretty much know not to be true in a significant enough percentage to make this claim), or that university press editors are too [insert uncomfortable adjective here] to make use of a resource that would directly and without question assist them in their job of sifting through stacks of book proposals (the preponderance of) which have all been polished enough to get the job done (something I refuse to believe).

Truschke goes on to offer a couple other reasons embargoing your dissertation is a waste of time.

There’s something in here about a two-year embargo being the norm anyway which isn’t enough time to produce a monograph so why bother? To which I say “Interesting. Love to see your data there.” My university allowed any period you could name, and I think you’d be hard-pressed to find an historian who wants to go up for a TT position unable/unwilling to revise and submit a proposal in four to six years (which is the real norm in practice, as far as I am aware). Plus, you can always extend the embargo.

There’s a long tangential section about the current economic climate of library acquisitions, which doesn’t share anything new until it gets to Truschke’s discussion of a company called YPB which apparently flags first books that began their lives as dissertations. We don’t really get any of the data required to assess just how significant this is, however: not how prevalent YPB’s presence is in the total academic publishing pie, not how they know a book is a revised dissertation, not how many university libraries use/know about/care about their existence. This is a throwaway section for me (though it’s also important, I think, to note that Wikipedia lists a hundred and two university presses in the United States, eight of which serve as the basis for her article. Truschke says she interviewed big ones. Considering the difference between Duke UP (120 titles and 40 journals annually) and Kent State UP (30-35 titles annually) is so disparate, I might expect market forces to act on them differently: this study has some data on p. 372 regarding this).

Equally unhelpful is this little gem towards the end:

“[S]ome university press editors that are concerned with an online dissertation adversely affecting book sales favor takedowns over embargoes . . . Ten years ago, Harvey said, taking down the dissertation from ProQuest was required for authors publishing with Stanford University Press . . . I wonder, however, if many junior scholars underestimate their ability to disagree with the press publishing their book and perhaps feel pressured to take down the dissertation when they would prefer not to do so.”

The issue here isn’t what to do once you’ve got a UP book contract. Embargoes are enacted to increase our chances on the front end–to get the offer in the first place. Plus, if Harvey wants to publish my first book but our dealbreaker is that I want my dissertation to remain online, I’m not going to be all that concerned about finding another home for the manuscript in the near future. Which Harvey clearly understands: “These days, however, the press concedes that authors hold varying views, and they will not insist on a takedown.”

The larger problem here, of course, is the murkiness of the whole enterprise of academic publishing. There has yet to be (to my knowledge) any robust statistical evaluation of the interaction between the open-access phenomenon and university press contracts that moves beyond “lets talk to the UP editors/directors/someone ‘in the know.'” Let alone one that is able to account for all the other forces acting in the field (which Truschke mentions at different times)–the contraction of library budgets, the reductions in and changing criteria for TT hirings at universities, piracy, etc., etc.

In the end, then, here’s the clearest formulation of Truschke’s argument: embargoing your dissertation doesn’t seem, in most of the cases university press editors were willing to share with me so I could write this piece about a practice that directly comments upon their access to the very material that would allow them to do their job to its fullest, to have any negative or positive benefits. Because even when seven percent tell you it matters whether your dissertation is freely available, their not really telling the truth. Except for right now, to me.

What we are left with is either a) statistical evidence like the kind Truschke (or this study she cites) is using, which mostly doesn’t tell us anything all that useful for those considering embargoing their dissertations, and b) anecdotal evidence like the kind Truschke offers which says not to worry. Well, you have your anecdotal evidence. I have my own. And until someone comes along with some more persuasive data I’ll keep my embargo, thank you very much.

I’ve got an essay out at Motherboard on the history of transhumanism and its rhetorical godfather, FM-2030.

I forgot to share this when it went live. It’s an essay published in the Chronicle of Higher Education in September on that behemoth of the anti-plagiarism business, TurnItIn.

Zoltan Istvan is running as the Transhumanist Party Candidate for the 2016 Presidential election. A sandy-haired, genial, passionate father, he’s landed at the forefront of the political transhumanist movement here in the United States over the last year or so. Articulate on the fly, he advocates the leveraging of radical scientific thinking and technological progress to boldly transform both the world in which we live and the bodies we inhabit. He’s seemingly indefatigable, doing interviews, writing essays, and talking to anyone who appears receptive to listening about how we can live forever in a better world, shepherded by artificial intelligence, if only we are bold enough to try for it. He’s a man who enjoys a glass of Laphroaig at the end of the day, is plugged in enough to know how Google’s SEO works, and is practical enough to focus his energies where they will do the most good for transhumanism. He was also kind enough to take some time out of his day to talk with me via Skype. We talked for almost a full hour, though he had only agreed on thirty minutes.

*The following was edited for length and clarity

Thanks for joining me here, I really appreciate you taking the time to talk with me for a bit.

Glad to be here.

So I’ve read most of your interviews and political writing, and I don’t necessarily want to rehash at length what you’ve said elsewhere. I’ll toss some links up of your recent stuff at Motherboard and Gizmodo and Medium and Esquire so people can check them out. That’ll free me up here to try to fill in the empty spaces, if that’s ok, and will give you the chance to cover some new ground instead of reiterating the same old thing?

Sounds great, yeah, whatever you want.

But let’s start briefly at the beginning. I think one of the challenges that you have faced and will continue to face is that transhumanism evokes so many different notions, and can be hard to encapsulate especially for the person who’s never heard the word before. So when I think about transhumanism—either as a political ideology or philosophical framework—I almost automatically follow Max More and Steve Fuller, and re-characterize adherents and opponents of transhumansim as Proactionaries and Precautionaries, respectively. If you’ll allow me to define them as I understand them quickly: Proactionaries pursue an agenda of calculated risk in using science and technology (via sometimes seemingly drastic methods) to change the basic living standard of humanity for the better, but also pursue extropian goals like virtual reality, or biohacking, or even a post-human future where we radically modify our bodies to live between the stars rather than huddled up next to them. The are, in other words, pro-action. Mistakes are inevitable in such a program, proactionaries argue, and must be accepted as the price of doing business (though we should certainly try to minimize them). Precautionaries, on the other hand—the opponents of transhumanism—seek the minimization of risk and damage (to humans and their social systems, animals, and the Earth) above all else, and stasis as more important than progress, and so see the Proactionary agenda as inherently reckless and probably resulting in the destruction of the world by grey goo. Thus, they advocate precaution. Is that a more or less fair way of thinking about practical Transhumanism and opponents of its agenda, or would you add to or refine or correct it for me?

You know I would say that’s an incredibly accurate way to reflect upon it all, you definitely have those sides and yeah, the way you said it is probably the way I would write it in an article, so yeah, that is perfect.

So why is Transhumanism a viable political ideology for the first time in 2016 and for instance why aren’t we having this conversation in 2004 or 1996?

Well, I think a lot of it has to do with, and if you’ll just permit me to be honest, the personalities that arise in the movement. There have been some enigmatic figures in the last twenty years in the transhumanist movement but they may not have been that savvy in using technology to get out their message, or they may not have been that savvy with social media. Or the social media environment didn’t exist. I think there was always a political element of transhumanism. I don’t think any transhumanist didn’t want to see, for example, a transhumanist president, or a transhumanist congress. But what happened just in the last few years, with Facebook, and Twitter, and all the other social media platforms, is you have actually have a real opportunity to voice an opinion that can get out to the masses without necessarily being, for example, world famous, or having billion dollars. So I think in many ways what has happened is transhumanism has kind of evolved to where a younger generation of transhumanists has emerged and are using social media to advocate. And that has changed the politics, because all of a sudden instead of just having a couple academics from the Ivory Tower talking you now have a social movement that is online, and it’s powerful. And it can go viral very quickly. So that’s why I think transhumanism has become political in the last year or so, or even two years. But it was always, in my opinion, political to begin with. It’s just nobody was able to get out their voice, and so nobody really tried.

Sure. I actually buy that a hundred percent, and that feeds perfectly into the next question I had for you. One of the things that intrigues me about Transhumanism as a political movement is the potential it has to violently (and in my and probably many other people’s views, necessarily) disrupt the current, entrenched two-party system. It’s been written about as a kind of ninety-degree revolution, from a left-right characterization to up-down one (following, of course, FM-2030’s notion of Upwingers and Downwingers). They say it appeals to people (young people, especially, as you say) because transhumanism talks about issues they find more relevant and pressing in the second decade of the twenty-first century (like open-source issues in economics, or biology, or information) rather than (what they see as) the constant rehash of “stale” issues (like perhaps the legitimacy of the welfare state or marriage laws or immigration or whatever). Would you say this characterization, this ninety-degree revolution—is a facile—if catchy—one, or have they hit upon something profound?

Well, I there’s a number factors here. To begin with they’ve definitely hit upon something more profound. I think (and kind of going more into social media) the younger generation, which is now the majority, I would say, of the transhumanists movement—which potentially could be millions around the world at this point—are sort of fed up with typical issues. They’re not really thinking of marriage laws, or social security—ok maybe they’re thinking about gay marriage laws—but they’re not necessarily thinking about the typical “Let’s have kids, let’s have a two-car garage, let’s have a mortgage.” They’re ready for something much more revolutionary, which is very typical of young people to begin with. They want something that is considerably different. Something that appeals to their youth, and that is something that really can’t be underestimated, because it’s absolutely so pivotal in everything that I’m seeing on a day-to-day basis. And so what’s happening is they just don’t care about social security—it just doesn’t affect them—what they care about it are radical things, like what are going to be the ethics of or morals in virtual reality sex? How is that going to change personal dynamics? What about space exploration? Wwhat about bionics? Can I run a hundred miles per hour when I have a certain type of exoskeleton suit? You know, these are the things that matter to this younger, upcoming generation. And that’s why all of a sudden people are very interested in it from a political point of view and wanting to say “Well, where can we go as a species?” That’s what’s exciting, that’s what’s important. A lot of the older transhumanists don’t see it that way, and are still debating stem cells and still looking at some of the older issues, whereas the younger generation, they just want to go headlong into some crazy things and that could involve all sorts of virtual realities and stuff like that. Which we don’t really have much ethical basis for or experience with; we’re just going down the road. The other day I did an interview with someone and she was telling me about how she had known a person who had some kind of virtual experience and was raped during that virtual experience and I thought “Well, we don’t have any kind of laws for virtual rape yet.” This is the kind of thing that the younger generation is very interested in discovering, and that’s where I think a lot of this kind of new political thought is going. When you compare something like that topic to social security, which most of these people haven’t even paid into, they’re just not interested. So that’s really again what I think is happening with the whole movement; it’s shifting to more exciting things that are happening in the evolution of politics as we [transhumanists] would know it.

So last thing before we move on to your particular stance on the issues. Besides a tendency to take the long view—and I’ve seen this kind of take shape slowly over the last six months or so as you’ve written more essays and articles in various spaces—Transhumanism holds tight to a certain optimism–in people, in technology, and in the future–what do you specifically say to people sets transhumanism apart from other political philosophies?

Well, I think the one thing that really sets transhumanism apart, and again this is entirely my opinion, my campaign opinion—it’s not necessarily the Transhumanist Party’s opinion, but I do believe and I think most people are on board with the idea that we can solve every single problem in the world with science and technology. Now that’s a very bold statement to make, but I do believe it.

Yes, it is.

The example I use is that MADD (Mothers Against Drunk Drivers) one of the largest nonprofits in American have been trying to stop drunk driving accident deaths which are tens of thousands every year by telling kids not to drink. But the real way to stop it is to not have people driving at all. And this is a classic technological fix to a very serious problem—I’m a father with two kids—that we’re all grateful for. I believe it’s a sort of metaphor for the entire transhumanist movement that ultimately science and technology can fix everything. Ok, not necessarily “fix,” but at least “make better.” It can at least help every single problem we have and that’s a very different [political] ideology than we’ve ever had before. The idea that we would put all our eggs with science and technology and not some other political ideology. That we would almost hold science and technology as the answer to all our problems. I think that separates political transhumanism from other types of politics that I’m aware of.

I love that example that you give because the first thing I think in terms of a technological fix to drunk driving is “let’s put a breathalyzer into every car,” but in fact one of the things that you can do is eliminate the driver as an entity from the get-go and that precludes all these other issues that have been plaguing us for decades and decades. So I wanted to move onto some shorter questions if that’s ok with you and hit some particular political stances and issues. I think another of the challenges you’ve faced and will continue to face over the next 18 months is that you’re advancing a political philosophy you want to become a viable party perhaps in 2020 or 2024, but you’re also an individual with particular beliefs. I imagine when you get questions about specific policy issues you’ve got to think for the Transhumanist Party but also yourself as a candidate. As you just said. Additionally, I know you’ve written that you don’t really expect to win a year from November. So feel free to punt on any of the following if you simply haven’t had a chance to formulate a political position yet. The first thing I wanted to turn to was this question of a jobless future. Easily one of the most often-repeated fear of a technologically driven future is that as machines get smarter and more capable, human jobs will inevitable be destroyed by the tens of thousands. You see this argument made about the auto industry—both in manufacturing and truck driving (most recently at Medium and Gizmodo)—but regarding other industries as well. Indeed, there’s a robot named Baxter developed by Rethink Robotics who recently worked 2,160 straight hours on an assembly line in Pennsylvania. It only cost $25,000 to implement, meaning it works for $11.57/hour. What do you say to folks who attack the optimism of the Transhumanist agenda by pointing to this potentially jobless future?

Well, you know my entire program with this is I’m trying to change the culture of how people view themselves and view the world. There’s no question that we’re going to have to change this idea that we all go to work at 9-5. It doesn’t really matter who you are—whether you’re a journalist or doctor or truck driver or a waitress—all jobs will be replaced. Probably the President’s job at some point will be replaced. The idea is we need to find a way to enjoy living a different kind of perspective, we need to accept that human beings are no longer going to work, that there’s a standard of living that’s going to be acceptable—you know this is why I ultimately endorse a universal basic income, I also endorse universal preschool and a universal college education. People need to become educated in a culture that wants these things so they can see a bigger future than just this 9-5 grind, which at least in America and many other countries we’ve sort of been programmed to accept. That’s not going to be the program in 20 years; the program is going to be “What can I do with my lifespan that makes me satisfied that is creative, that is artistic, that is culturally relevant?” To be honest with you I don’t have all the answers regarding what that future is going to hold and how people are going to be different, but one thing I know for sure is that people must absolutely change. And when I say “change” I mean they’re going to have to accept a new standard of living, a new standard of how they view themselves that has to be outside of their paid profession. So it’s totally critical that people start to take that step down that path. It’s very possible we just end up being ten billion people who meditate half the time, or ten billion artists. I don’t know what the future’s going to hold but it’s inevitable and it’s going to take a complete revolution in our cultural outlook to make sense of that and to be happy with that. But I think once we accepted it life is going to be far happier and far more fulfilling.

That sounds like a radical shift. You’re talking about a whole new ethos for living, a new set of morals and values that are no longer defined by what we do for a living. I think it’s an exciting prospect for the future. Let’s build on that formulation of a new cultural framework for a moment. Much of your writing and speaking inevitably turns to radically extended or indefinite life spans. When death becomes an unusual state of being, will it be easier to abolish the death penalty as cruel and unusual punishment, and for that matter what happens to lifetime prison sentences for those who are prone to recidivism when we’re living a thousand or ten thousand years? What do we do with those people?

So there are two things here. In general, and in theory, I have been a supporter of the death penalty under certain circumstances. However, I’m no longer a supporter of it under the transhumanist agenda, and so when it comes down to my policy I’m not supporting that anymore. It’s very difficult to support the death penalty in a world where everyone’s going to eventually be living indefinitely. Realistically, in ten or fifteen years we’re probably going to have cranial implant technologies that will be able to change the basis of personality, so these criminal things that people want to do might easily be either taken out via some kind of behavior-modification technology or re-engineered through some type of genetics. Additionally, we’ll probably going to be able to have this kind of setup where you’re constantly being monitored. We’re already moving to a surveillance society. You’re just not going to be able to commit the same crimes you once wanted to do because you’re going to be observed at every single moment of your life when you want it or not. So this whole idea of crime is going to change radically over the next ten to fifteen years. And I advocate for using technology to do that, because I believe every human being—even those that are the most evil or criminal—can be changed into something that is much more useful to society. Now of course, if they don’t want that change maybe there needs to be some type of place where we could leave them. In fact in my novel [The Transhumanist Wager], there was one section that I took out of the book—it just was kind of a little too controversial—was creating nations where criminals would just be left.

Sure. Parts of Australia started their life like that.

Yeah. It’s not a punishment in a sense. The only thing is you just can’t come back. You can forge your own life, within the system. So at this point in time I don’t support the death penalty anymore. What I support is using technology to rehabilitate people and modify the things in them that don’t work well in society. Obviously if you have murderers that can’t be something that’s allowed. So people will have to accept that either you will have to be changed through some type of chip or some type of genetic engineering or you need to be withdrawn from society and put on an island. The one thing we can’t do is spend as much money as we’re spending on prisons. That’s absolutely insane. We should be spending that money on education or life-extension research. If we took just a fraction of some of the money spent on the prison system in America and put it towards life extension science we would literally triple the amount of money that’s going towards the industry right now. And that’s just from the prisons. In the age of unlimited life spans I think we need to rid ourselves of criminal intent and acts through technology.

Well that actually sets me up perfectly for the next question. So science and technology research in the United States saw federal funding somewhere in the realm of 135 billion dollars and change in 2015, with much earmarked for defense-related activities. What should that number really be?

Well, look, the defense industry is a multi-trillion-dollar industry. And I think the amount of money that is going directly into the life-extension industry is in the realm of about eight billion, and half goes to Alzheimer’s anyways. And not that I would consider Alzheimer’s research “life extension” research—it’s good that we’re spending money on it, but if I were to look at a billion dollars going into Google’s “Calico” program then I could say it’s going directly into life-extension research. The United States has got a GDP, and the numbers fluctuate, but at any given moment the number is seventeen or eighteen trillion dollars, and we [in my campaign] feel that we should spend one trillion dollars over a ten-year period directly into the life-extension industry. Nothing like that has ever been done. This would be a hundred, two hundred, three hundred times more than anything that’s every taken place. And it would completely revolutionize medicine in the United States. Sort of like Obama’s brain initiative, which is awesome, but it’s only three billion dollars, and honestly that’s pretty small when you consider that the Iraq war cost approximately six trillion [counting interest over the next four decades]. So what we’d like to do is take about a three or four percent of the annual GDP and spread it over ten years—so it’s really a fraction of a percent, and we could revolutionize health care. If America values itself at around 40 trillion dollars, to spend two to three percent of our net worth over a decade to give our citizenry a solid chance to discover the very best life extension we can come up with with that money, we should. Most experts say that even with the few billion going into life-extension research now we’re probably going to reach some type of ongoing sentience in the next twenty or twenty-five years. A trillion would funnel a hundred times that commitment into it. We could at least speed up the progress, and find ways for humans to overcome their biological boundaries like dying. And I’ll tell you about this though I haven’t written about it again: the one thing that I’m going to advocate for at great expense to my libertarian base—not that I’m libertarian, but I have a lot of libertarian friends—is something that I’ve written an article about that I call the “Jethro Knights Life-Extension Tax”. And what I had suggested and what we’re going to campaign on was that everybody in the world donate one percent of their net worth one time. One percent, so if you’re worth ten thousand dollars you’d donate a hundred dollars one time, and so one, and that would contribute many, many trillions to this research. We as a world would come up with very quickly the resources to overcome biological death. I’ll send you a link to that article. When I released that article about a year ago people sort of freaked out. It’s so difficult to campaign on taxes at all, and it’s not something I necessarily think would ever get passed, but it’s very illustrative of how such a small portion of who we are as people—just one percent of one’s net worth and we could change the fate of seven billion people. And the great thing is it’s really favorable for those who don’t have much money—even at minimum wage you could contribute your one percent in one day’s work, and guarantee your immortality. This is a tax that’s going to upset the rich more.

I appreciate the link, I’ll include it. I know we’re running up a bit on time here, but I wanted to ask you quickly: You’ve mentioned in the past that at the state level there are some transhumanists running for office. Are there any, in your eyes, “closet” (or semi-open) transhumanists in Congress right now (and perhaps they don’t even know it yet) that you see as potential allies should you win the White House? Al Gore seems the closest and most obvious mainstream politician of the last ten years I can think of.

Yes, Al Gore is absolutely a transhumanist, he’s used the word transhumanist numerous times in his books, he helped launch Jason Silva’s career. But we have not recognized anyone else. It’s funny, my advisors and I just had this discussion about a month ago—there are a number of Congresspeople who are very pro-science, but I think if you asked people most would admit to being pro-science. One of the things is that a lot of the democrats that are pro-science mean it from an environmental perspective, and of course that’s great because we want to save the world too and want the earth to be pristine. But I don’t know if they’re pro-science in the way that I am trying to advocate for, as in trying to advocate that we replace human hearts with robotic hearts so we can eliminate heart disease in America. That’s the pro-science attitude I’m looking for in politicians, and I have not yet seen anyone. What I have seen is people putting more money into science and more money into technology, which is wonderful, but they haven’t thought through what that means when it comes to upgrading human beings into something very, very different. And part of the reason is as soon as you talk about these concepts that comprise transhumanism, you bring up these major other issues like overpopulation and social security, which are just such land mines for any politician. As soon as you advocate for an indefinite life span without trying to also counter the other people who are going to say “Well, great, how are we going to pay for an entire generation of people who are never work again.”

Absolutely.

This is one of the reasons that transhumanism faces a real challenge and uphill battle in politics, because while the idea of it is probably appealing to most people who would say “Yeah, I want to be perfectly healthy and I want to live longer,” when you point out that everyone on the planet wants to do that giving you twenty billion people with a large chuck potentially on social security, most politicians are reluctant to talk about it. I do have a campaign coming up here beginning at the Huffington Post where I will start saying things like “Hey, Hilary Clinton—are you a transhumanist?” Or something like that, and hopefully it’ll get people to say “Well, what does that mean? How far are you willing to go on these kinds of issues?” And eventually, if we end up conceding, the small group of transhumanists will probably end up supporting some democratic candidate where we can pursue science and technology issues in a secular-minded way. So unfortunately I can’t answer your question and say there’s anyone out there right now. The problem is all the great people who should be running for politics are scientists and they just don’t want to be bothered with this stuff. And that’s another sad thing. I recently wrote an article saying that we should make it a law that you can’t have so many attorneys in office. You must have a complete, broad, representative population.

That’s an interesting idea.

Yeah. If you have 15% scientists in the world, then you should have 15% representation by them. If you have 15% engineers in the world, we need 15% of Congress to be engineers. Right now it’s skewed towards attorneys and the kinds of professions that, you know, generally aren’t pro-science or pro-technology but pro-legal things. And that has also been very disruptive to society.

I haven’t seen it anywhere specific, but for some reason this strikes me as a very FM-2030 notion. A neat, proportional representation I would not see as out of place in either Optimism One or Up-Wingers.

Yeah, and you know I wrote about a related idea in my novel and it just amazes me that this isn’t already the case. There also needs to be a law that the female-male distribution in Congress should be pretty even, with incentives for females to run if it becomes unbalanced. I find it crazy that we have a Congress that’s still dominated by mostly white older males. Times are changing too quickly and it’s not able to keep up. The biggest problem about politics is that science and technology are making those same old white males live longer and longer and hold onto their power longer and longer, even if they don’t support the science and technology. It’s absolutely critical that we bring in diversity, and it’s absolutely critical that if we want democracy to work we do our best so that everyone is represented according to their numbers. Not just the same people who have kind of been in power since the [nineteen] fifties and are basically advocating for almost identical policies. The only difference is they’re doing through their iPhones and pretty soon they’ll be doing it through they’re cranial implants. And something is different because technology should force ethics to change; that’s what we were talking about in terms of making the death penalty illegal. At one point I did support it—if someone had murdered my entire family, sure, that person deserves the death penalty. However now I understand that, because if we have but withhold the technology to change that person then that would be me murdering that person. So, again, this kind of goes back to when you were asking what’s the difference between transhumanism and other political parties. It’s that we honestly believe that science and technology can literally solve all these problems. But we can’t get stuck in these old ethics, with cultural baggage, as I often refer to it. We need to let the technology and science lead the way. We need to listen to it.

And let science and technology drive a new ethical framework rather than recapitulating the old one and perpetuating it to infinity. Hmm. Well, thanks for answering those questions. I was wondering if I could take just a couple minutes here at the end to just indulge a little with some questions you might not regularly get asked, and so feel free to take a pass on any of them. You said recently you think there are at least 150k and perhaps a few million transhumanists in the United States right now. Your campaign has been slowly gaining attention over the last few months as well. How many hits is zoltanforamerica.com getting these days?

You know, the main website is zoltanistvan.com/. To be honest, we’re not getting that many hits—I haven’t looked at the numbers for zoltanistvan.com recently. But I can tell you that—and people ask me this all the time—they say hey, your website’s kind of old and not as savvy-looking, and part of the reason for that is my campaign doesn’t get as much funding as even other third-party campaigns. Transhumanists, because they’re so young, they don’t have that much money, so we’re just dealing with it as well as we can. But I can tell you last week, that between the interviews and articles I did I thought we were somewhere between three and four hundred thousand views of my stuff between a Popular Science article and an Esquire one, and something I had at Vice, even if the website might have only been a few thousand. Now obviously that doesn’t necessarily translate into supporters. But it translates hopefully into recognition. At the end of the day I’m not expecting in any way to win. What we’re really trying to do with my campaign, at least in 2016, is to spread transhumanism. We generally do one to two million views of our campaign every month.

I think that’s pretty good.

Yes, no, it’s great! It’s fascinating. I worked it out last year, and this was before my presidential campaign, and it was pretty disappointing to my wife. She said, “Ok, in 2014 you had approximately twenty to thirty million views.” There were a couple of articles that just went completely viral, they were picked up I think by seven of the top ten Chinese sites. There was the one on ectogenesis. But we were asking ourselves, in terms of finances, “How many ads did I sell for other people?” and we came up with something like probably seven hundred thousand dollars. Of course I made a small fraction of that from my writing—so I was making some other people very wealthy. But the idea is that the message is getting out more broadly. You can see through my columns that the transhumanism movement is changing. People are hearing the word again and again and again, and once they hear it they start using it. It’s not of course necessarily only associated with me in any way. But that’s how we’ve been measuring our success, as opposed to donations which have generally remained small. We’ve been much more concerned with determining how the media is handling it all, because at the end of the day what’s most important for myself and transhumanists is that we build a culture that welcomes transhumanism as opposed to a culture that welcomes dying and going and meeting Jesus or something. We’re trying to make it so that transhumanism can work within the culture already established here in America. And if the culture’s there then people will begin to say “Well, why don’t we have more robotic body parts to end heart disease and why don’t we have exoskeleton suits to end disability?” And if we encourage this culture and get people onboard to embrace it, then pretty soon you’ll see us go back to your question about congresspeople who say “Yeah, I’m also a transhumanist”—or, actually, they’ll probably say something like “I support transhumanist technology for the better health of Americans.” And that’s a very important thing, so we spend almost all our time trying to make an impact in the media in the hopes of effecting change on that framework for Americans. And we think in two or three years if the movement continues transhumanism will be a household word. One of the things I’ve been totally impressed with is that in Europe they’re totally throwing the word around like it’s normal now. And I can tell you two or three years ago it was not a normal.

Well, I think it’ll be exciting to see how it grows as the election cycle begins to ramp up. Ok. Last question for you. I’m reading Kim Stanley Robsinson’s Green Mars right now. It’s pretty great, though Red Mars was better. What’s the last book you read purely for enjoyment, and what did you think of it?

You know, I’ve got to be honest. If Ray Kurzweil asked me to read his book I wouldn’t right now. I check my email at two, four, six in the morning, and we also have an infant so it’s just been all coming together at once. Plus, I’m reading and writing all day every day, so it just takes too much of a toll. But one thing I still manage to do is watch a documentary every single night, or most of one. I used to be a documentary filmmaker. I worked for National Geographic, doing mini-documentaries.

Oh yeah, I read that actually.

Yeah, so usually around eleven or so I’ll get to sit down with a glass of scotch and that’s how I unwind. And the one I just watched that was great was called The Singing Revolution. It’s about how Estonia was born. Essentially, they made use of a nonviolent way to cause a revolution, and they gave birth to a nation by singing. I didn’t know this story at all. And when you get a million people singing in front of an army, you can’t do anything. It’s a very powerful documentary. I usually get up around seven in the morning and work through to ten or so at night, so I really look forward to that time where I can enjoy someone else’s ideas and explore what they’re thinking.

Zoltan Istvan’s personal website

That was a pun. This is a post about bees.

So I’ve got this fascination with bees. Not up-close, because I’m afraid they’ll sting me and I’ll die. I got stung fairly regularly as a wee one (as one would expect growing up in the country in Minnesota) but also more than you’d think as both a teenager and young adult (no real satisfactory explanation for this). Three I remember vividly. Stepped on a nest while mowing the lawn, which wouldn’t have been that big a deal but I’d accidentally just run it over and was mowing barefoot at the time. They were pissed, and I rightly got hit about half a dozen times. Then once when I was older in the face, which was as initially terrifying as you’d expect but faded pretty quickly, and then finally once in the arm which (because of the latter) I figured would be no big deal until it swelled up so much I couldn’t bend my wrist for most of a day. So I keep my distance these days, and admire them from afar.

Bees are infinitely interesting. They’ve been around for millions of years, and navigated potentially cladogenetic environmental changes time and again by positively selecting advantageous traits very rapidly. Darwin was fascinated by them. They confounded human ingenuity for hundreds of years. I wrote about how they can help us be smarter in designing elections a while back. I guess, to me, they represent some ultimate form of crowdsourcing the decision-making apparatus, and serve in so many cases of the power of collective intelligence.

So recently, I picked up Hannah Nordhaus’ The Beekeeper’s Lament: How One Man and Half a Billion Honey Bees Help Feed the World. To be completely honest, I wasn’t expecting that much from it. Some overly dramatic language on how global warming/pesticide use/habitat loss has and continues to decimate bee populations and that’s going to lead to the end of life as we know it. Recent years have seen staggering bee losses in the United States, as any non-sequestered individual knows, and I assumed that would be the tent pole of the book. As a reader, such treatments bore me to tears. As an animal lover, I wasn’t really looking forward to a couple hundred pages about here’s another way I need to be ashamed of my species. As an historian of science and (in some ways) strict Darwinian, I knew it would probably be overwrought. Nature, for good and ill, finds a way. Species adapt, or they don’t, and the world keeps on turning. If humanity accidentally nukes itself a thousand times over, one or a hundred or a thousand million years from now life will emerge and start again.

Thankfully, refreshingly, astonishingly, even, Nordhaus manages to eschew that caricatured narrative which so plagues other science and nature writing (even by people who should know better). Certainly at times The Beekeeper’s Lament is a paean to a simpler time. Alternately, too, it might strike some occasionally as a hand holding a megaphone prophesying a looming Armageddon. Here and there, heartbreakingly, it is unavoidably Sinclairean in its portrayal of the honey-producing industry and the life of the average bee in America. It is, in fact, more than most a many-faceted narrative of hardship, loss, hope, triumph, tranquility, anxiety, sacrifice, community, loneliness, and stubbornness. It is, in other words, a narrative of the American beekeeper.

If that kind of exploration interests you, and you have an appreciation for consistently clear writing marked by a strong authorial voice, you’ll love The Beekeeper’s Lament. Nordhaus demonstrates a talent for making her characters come to life, which is quite the feat given how boring we know most of our fellow humans to be. John Miller, a beekeeper from California who also spends time in the northern plains, is the simultaneously irascible, gregarious, obsessive, laissez-faire, and above all committed central thread of the narrative. This is a book that, as I’m sure Nordhaus would admit, is as much his as it is hers. And he is, if not always likable, certainly insightful and interesting.

It’s a book filled with the minutiae (and history) of beekeeping, bee physiology, bee habitats and ecosystems, and the honey marketplace. The two most compelling points of the narrative are at once simple and revealing of the past, current, and future prospects for bees and all of the constituent ways in which their lives intersect our own.

The first is that the beekeeper hangs on by a thread. Varroa mites and pesticides contributing to colony collapse disorder (CCD), trade pressures (and laundered honey from China), disappearing habitats, the monoculture pursued by farmers, and labor shortages—in addition to what is at times an astonishing dearth of knowledge about the basic needs and lives of bees on the part of zoologists and biologists—all ensure that the beekeeper, more than most, lives a precarious existence. Beekeeping is an occupation, a way of life, really, that requires one to expect just as many bad years as good years. Pollination (of almonds, oranges, etc.) would be a much more hassle-free, lucrative way to put their bees to work. One doesn’t go into the bee business to make money, as the current demographic trends of the industry in the last two decades reflect. Beekeepers are getting older, and many are finding it difficult to find individuals to continue the work in the next generation.

The second is that for bees (both individuals and as a collective) life is an intensely focused affair that for all but a few will be almost certainly violently cut short. For some only recently understood (but many more often hidden) reasons, as a species their existence is a continual massacre. Nordhaus reiterates the common point that those who have in recent years followed the saga of the bee already know: that without the honey industry, the bee would virtually disappear from our daily lives. John Miller has about ten thousand hives holding around eighty thousand bees apiece, for a total population of three quarters of a billion bees. But in 2004 he lost thirty million bees when a truck transporting hives crashed. In 2008 he lost twenty five percent of his hives to CCD. Acceptable yearly loss before 2007 was fifteen percent, which is a lot when you consider there are some two trillion honey bees in the United States. Now, it’s thirty percent. Hundreds of millions of bees die every year, and will continue to do so. Oftentimes, honey bee outfits only survive because Miller and others raise queens and ship them around the country especially for repopulation after a colony collapse (in fact, it’s become an industry in its own right). This remains one of the most powerful lessons of the book, and speaks not only to the stubborn resilience of the American beekeeper but to the horror of an industry which views millions of deaths as part of a cycle that constitutes the new normal.

What would happen if we put the brakes on it all? Some conservationists would argue (usually the same ones that claim we need to keep eating beef or the cow would go extinct, so we’re really doing them a favor) that the honey bee would go the way of the dodo, the golden toad, the zanzibar leopard, or the javan tiger if we no longer acted as shepherd in the cruel, modern world. Varroa would prove their demise, or habitat loss would finish them off. Yet as Nordhaus also ably relates, bees remain, more than most, a resilient species. Some few variants would undoubtedly show adaptations which would allow them to survive and even flourish in an otherwise bee-less world. Whether we’d have honey for our consumables (or honey we’d want to use) or the two hundred billion dollars’ worth of crops bees pollinate each year remains a far less relevant story, evolutionarily speaking (except, of course, to the beekeeper). Or maybe there’s a third way, where we decide responsible cohabitation of the land with other species doesn’t automatically constitute endorsement of some anti-human narrative. Or that this is an either/or proposition. If that means I pay ten or twelve of fifteen bucks an ounce for honey, then I guess that’s what I’ll do.

And in spite of the endless cycles which seem to govern the life of the honey bee as a species, they are, as I’m sure Miller or any other beekeeper will tell you, unique and distinctive in their lives. Peel back the superficial, peer into the microcosmic, and you’ll find the moods, the whims, the predilections of the individual honey bee. And that, friends, is why Kundera serves as a better title for this post. That, and Nietschze has always seemed a gloomy bastard to me.

*Header image from http://japers.deviantart.com/