Welcome to PART 3 of our ongoing series here at the slowlorisblog, 42 STEPS TO A BETTER WORLD. That time, it sure is flying. To think we’re already 1/14th done! At this rate, we’re looking at a finish date of 2019, and that’s way ahead of schedule. Today, we offer a radical proposal (accompanied by perhaps as many links as we’ve ever had in a single post): that we’ve been counting in a count(ha)er-productive way for millennia, and to offer an alternative way to do it and make the whole world a better place.

Here’s how most of us count:

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10

Here’s how dozenalists (also called duodecimalists) propose we should be counting. It is also the official sponsored counting system of the slowlorisblog from here onward:

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, X, E, 10

(many dozenalists represent the X as an upside down 2, and the E as a backwards 3)

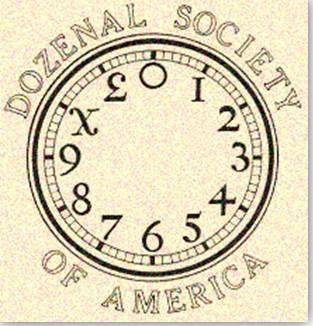

Both the Dozenal Societies of America and Great Britain propose that we should be counting not in base-10, but in base-12. Phonetically, they’d sound like this:

one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten, elv, unqua

(It is, in my opinion, a massive failing of the movement that most of them insist on forcing us to replace, conceptually, the Roman number 10 in their number line with a set of numbers that is in fact “12-large,” while phonetically retaining “ten” for the numeral X. Others have suggested calling the numeral X do. Whatever the case, it’s obvious that one of the largest obstacles to adoption is going to be pronunciation. Especially when it comes to large numbers.[1] But if we can put this problem aside for just a moment, we’ll see many potential benefits).

Historically, the way we count is more or less based on the number of fingers and toes we have. Other societies have counted differently: the Babylonians counted in base-60, the Mayans in base-20, the people of Papua New Guinea are said to count in base-6, the Umbu-Ungu in base-24, and various positional and other computational systems favor base-36. So counting in tens isn’t some kind of incarnation of Natural Law. It just happened, and we stuck with it.

Proposing any kind of change like this is sure to ruffle some feathers. It would cost a good deal to do, in addition to annoying parents who thought they knew how to count, Especially when little Umlaut comes home asking why mommy didn’t teach her about the number elv.

There are really two, not necessarily mutually exclusive, cases to be made here: that switching to the dozenal system would be a beneficent move in terms of everyday convenience, and that it provides mathematical benefits with larger impacts in that field of praxis. The former of these is the easier one to make, but it’s also much less convincing to the average reader. Convincing one generation to re-learn how to count so as to (mostly) benefit the succeeding ones rarely works. This phenomena affects not only knowledge systems, but technology. Look at the arguments to be made for switching to the Dvorak (or other alternative) typing systems. The latter of these, the mathematical benefits, are murkier, but still titillating. Let’s dive in!

Mathematical benefits

- Fractional representation: Fractions, in total number, digit-length, and common-use ones are, I think, inarguably simplified when it comes to dozenal math. Compare them for yourself below. The big takeaway for me is that 1/3 stops being a mess, and most of the other common fractions go from two or three digits to one. The only real backward step is that 1/5 goes from .2 to 0.24972497 (recurring).

| FRACTION | DOZENAL | DECIMAL |

| 1/2 | 0.6 | .5 |

| 1/3 | 0.4 | .333 (repeating) |

| 1/4 | 0.3 | .25 |

| 1/5 | 0.24 (repeating) | .2 |

| 1/6 | 0.2 | .1666 (repeating) |

| 1/7 | 0.1714285 (repeating) | .142857 (repeating) |

| 1/8 | 0.15 | .125 |

| 1/9 | 0.1333 (repeating) | .111 (repeating) |

- Recurring digits: In the real world, problems with factors of 5 come up far less than problems with factors of 3, and the the dozenal system brings with it a host of inherent properties making it superior to the decimal system.[2] That means recurring digits (and the rounding inexactitude they often require) come up less often. Nevertheless, the real benefit that in the dozenal system when recurring digits do come up, they tend to be much shorter than in the decimal system. This is because 12 sits in the middle of two prime numbers (11, 13) rather than, as 10 does, next to a composite number (9).[3] It also is the result of their respective factorizations (the process of breaking numbers down into all the small numbers which, when multiplied together, get you to the large number), where dozenal offers further benefits. The prime number 2 shows up twice in the factorization of 12 (as opposed to once in 10), and the prime number 3 shows up once instead of not at all. Basically, more primes = good, less = bad.[4]

- Superior highly composite numbers are those which have a greater number of divisors relative to the number itself. 12 is one of these. 10 isn’t even a highly composite number (those positive numbers with more divisors than every smaller positive number). This means the math, including but not limited to the two cases above, gets cleaner all the way around.

Everyday benefits

Basically, it makes counting better all the way around, in terms of weights (pharmacists and jewelers use a 12-ounce pound), measures (a circle has 12 divisions of 30 degrees, there are 2 sets of 12 hours in a day, 12 months in a year, 12 inches in a foot for carpenters) or money (the British pound system, but also American financial markets as they are based around a 12-month year). There are a host of others, that if you are curious about you can check out at the American Dozenal Society Education Resources Page. [5]

Thus, for children, it makes math easier to conceptualize and understand. For those of us raised on the decimal system, we can just use a calculator.

What a Dozenal World Would Look Like

Fans can join the movement and its (only semi-facetious) legislative proposal, the Dozenal Establishment Act.

Further Reading

Interview with Dozenal Society of American Don Goodman

The Dozenal Society of America

The Dozenal Society of Great Britain

A nice video introduction to base-12

[1] http://www.dozenal.org/drupal/sites/default/files/db4b20a_0.pdf

[2] http://www.dozenal.org/drupal/sites/default/files/db27309_0.pdf

[3] http://www.dozenal.org/drupal/sites/default/files/db4b109_0.pdf

[4] http://www.dozenal.org/drupal/sites/default/files/db4b211_0.pdf

[5] http://www.dozenal.org/drupal/sites/default/files/leech_thomas_dozens_tens.pdf